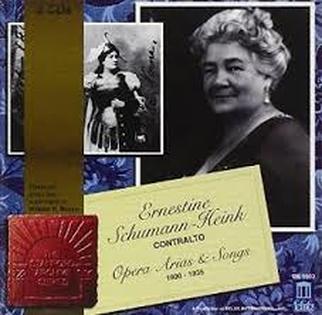

I won. I think my mother gave up because she was tired of the routine, dragging a truculent, dusty twelve-year-old to a piano lesson. That July afternoon was typical. I saw our black, three-holed Buick coming down the dirt road towards the stables at the Elko County fairgrounds. “I’m in for it,” I said to my best friend, Karen. We were in seventh grade and crazy about horses. My mother didn’t scold. She leaned across the front seat, opened the passenger door, told me to leave my bike, get in the car, and, no, I couldn’t go home to change clothes. It was time for my piano lesson. Not until I was seated at the grand piano next to Mrs. Watts did I see the dirt under my nails, feel the dust on my shirt, and smell the horse sweat on my jeans. It’s curious that after more than sixty years I remember that my piano teacher, Mrs. Watts, had been the accompanist to Madame Schumann Heink. I recently googled Ernestine Schumann-Heink (1861-1936) and, according to Wikipedia, she had quite a career: operatic debut in Dresden as Azucena in Il trovatore and final performance at the Met in 1931, belting out Wagner at age seventy-one. Wiki notes, “In the movies of the 1930’s, many a buxom opera singer/instructor/matron was modeled on her.” My question is this: How did Marie Watts, her accompanist, ended up in our cow town in the l950’s, married to Mr. Watts, a building contractor? I guess I will never know. Their house on Ash Street, a series of three flat roofs, classic mid-century modern, was built into a hillside. The piano studio was on the bottom floor, the dim light and cool room accentuating my horsey scent. My opportunity to learn to play the piano from an exceptional pianist lasted six months. Mrs. Watts started me with two instruction books, one of scales, boring and intimidating. The other, First Lessons in Bach, intimidated me even more. I was in one recital playing a piece called “The Bells,” which seemed to be pressing with feeling on the g key above middle c with the fourth finger of my right hand. What little practicing I did was fear-based. I hated the thought of disappointing both refined and patient Mrs. Watts and my mother. Other girls my age started taking piano lessons about the same time, but they went to Mrs. Clark, a flamboyant little lady who dressed in primary colors and taught girls to play popular tunes and watered-down classics. By high school, my friend Gail, who stayed with Mrs. Clark, could play the “Moonlight Sonata,” at a high school assembly. The boys were impressed by her athletic prowess, stretched fingers pounding chords up and down the keyboard, crossing the left hand over the right and back. Another friend, oldest daughter of the town’s favorite doctor, could play Bach on the violin, an incredible social liability. The brazen boys would put their fingers in their ears and make pained faces. I wish I hadn’t won. I know there is no point in dwelling on missed opportunities. I remember a quote from a character in The American by Henry James: “I have the instincts—have them deeply—if I haven’t the forms of a high old civilization.” I did want to become a cultured person, well-read, educated, and familiar with the arts. Eventually, I learned to love classical music. I became a college English teacher, which guaranteed a lifetime of reading good literature. But I have never become accomplished at anything. I am at the age of regrets and bucket lists. To have hectored my mother out of piano lessons from Mrs. Watts is the least of my regrets. However, when I turned seventy, I had a strong urge to learn to play the piano. So, I bought a piano. On the internet I found the name of my piano book with the ochre cover and antique lettering--Beginning Bach from Schirmer’s Library of Musical Classics. With some chagrin, I noticed my old piano book is listed as a collectible on Amazon.com. I found a piano teacher in Elko, a lovely woman who doesn’t seem to notice when I come in from Tuscarora for my lesson, slightly dusty from the drive. I don’t mind being a beginner. Actually, the going wisdom is that at my age it’s healthy to be learning something new. I figure if I practice an hour a day, by the time I’m eighty, I could be quite accomplished. Click on "Comments" above or below the post, then fill in the form, or click on "Reply" of another comment to add to that comment. SHARE on your Facebook or Twitter, hit the buttons: |

AuthorNancy Harris McLelland taught creative writing, composition, and literature for over twenty years and Conducted writing workshops for the Western Folklife Center, Great Basin College , and the Great Basin Writing Project . An Elko County native with a background in ranching. McLelland has presented her "Poems from Tuscarora" Both at daytime and evening events at the Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko. Her essay, "Border Lands: Cowboy Poetry and the Literary Canon" is in the anthology Cowboy Poetry Matters . Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed